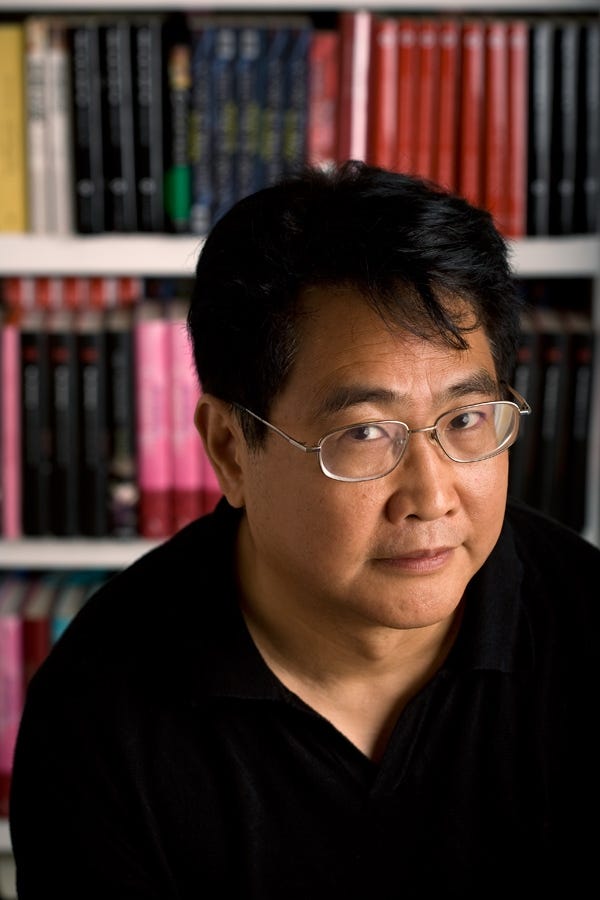

Interview with Qiu Xiaolong

The adventures of Inspector Chen Cao and writing about modern China

Qiu Xiaolong is a US-based poet and author of Chinese crime fiction who is most famous for his detective novels, the Inspector Chen Cao series. The setting for the series is contemporary Shanghai, in the years following China's reform and opening up. Inspector Chen Cao has a sensitive job; he mainly investigates crimes for the government hierarchy, which means that he must find the culprit, but also needs to be socially and political aware of what the investigation might reveal. Most importantly, he needs to act with care and discretion, because the wrong move may jeopardize his career and family.

The series follows a chronological order, starting with Death of A Red Heroine. Qiu returns to China frequently, and closely follows the social and political changes in China, and works them into each new novel so that they closely reflect recent developments in China.

His books have been very popular in the west, and have received many awards, and have also been made into BBC4 radio dramas. They have also been translated into Spanish, Italian and other languages.

On a personal note, I have enjoyed this series because it gives an inside look at what it is like to work in a closed system like China's. It is very hard, almost impossible, to get this kind of inside view in the English-language media, either as fact, fiction or reporting.

Following is the interview.

You started your studies initially planning to translate T.S. Eliot into Chinese after visiting the US. Then you switched over to writing about a Chinese detective in contemporary Shanghai named Inspector Chen Cao, who handled sensitive crime investigations for the political leadership, and wrote it in English. What made you make such a drastic change in your writing interests?

I translated T. S. Eliot into Chinese, including “The Waste Land,” “ Four Quartets” among many others, before I came to the United States as a Ford Foundation Fellow in 1988. At the time, my plan was to stay for one year at Washington University in St. Louis, a university founded by Eliot’s grandfather, to do research for a critical biography about T. S. Eliot in Chinese. Before one year was over, the Tiananmen crackdown happened in 1989. It totally changed my initial plans. Because of my support to the students in Beijing, I was put on the blacklist of the Chinese authorities. I could not go back, nor could I continue to publish in China at the time. That’s why I switched to writing in English. I wanted to write about Chinese society in the transitional period after the end of the Cultural Revolution. I thought fiction instead of poetry might serve my purpose more conveniently with the main character still being a poetry-loving intellectual, who thinks hard about how and why things are happening in China. But before that, I had mainly written poems, so I had problems with the structure of the first novel. That’s how the genre of the crime novel came to my rescue, as I could say what I wanted to say in the ready-made framework of the genre. To my pleasant surprise, my American publisher signed a contract for three books with me, and then from the first stand-alone novel, the Inspector Chen series has been developing.

Where did you get inspiration for creating the character of Chief Inspector Chen Cao?

From multiple sources. In China, I had, and still have, some friends like Chen, who have been trying hard to make a difference by working within the system, though they have an increasingly difficult time. And I also happened to know someone, who, like Chen, having majored in English literature, was state-assigned to a job he did not like in the Shanghai Police Bureau. Because of that, he told me a lot of inside information about the police work in China.

What are the constraints for Chief Inspector Chen Cao in today’s China which make his investigations for the truth different from other detective characters in other societies?

A lot. To begin with, there’s no independent judiciary in China. Not long ago, a debate broke out in the social media, raising the question as to whether the CCP (Chinese Communist Party) or the law is bigger. People in China all know the answer. So the Beijing authorities had to declare the question as a fake one. With the Party interest placed above everything—above law, Inspector Chen has a difficult job cut out for him. Being an honest cop, he still dreams of fighting for justice, so he has to walk a tightrope all the time. With the CCP revealing more and more of its true colors, Chen gets increasingly disillusioned and frustrated. Recently, as China is rapidly turning into a surveillance society much worse than in 1984, Chen finds himself too turning into a target of the state surveillance, but he has to work on in spite of all the troubles he lands himself in.

The backstory for the Chief Inspector Chen Cao series is the political and legal world in a rapidly changing China, where the society, technology, and social values are changing at a head-turning rate. How do you convey the scope of these changes to your readers?

For the backstory of the Inspector Chen series, you have summed it up well. From the very beginning, I did not set out to write simply a whodunit. Rather, I want to explore the political, cultural, social circumstances in which the crime and investigation take place. So for each of the Inspector Chen novels, I put the crime and investigation in a specific backdrop. For instance, the first book in the series, how the CCP ideology imposes double personalities on Chinese people, as a result, they have to wear political masks all the time, and how such double personalities lead to tragedies. In the following books, I explore such specific issues as the corruption under the one-Party system, the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution, the shadow of Mao, the pollution which became uncontrollable because of the authoritarian rule, the lack of judiciary independence, the horror of the omnipresent surveillance state and so on. As it is an ongoing series, I’ll deal with all these changes, and from time to time, I may also re-examine some of the issues in the light of the latest developments.

So far you have published eleven titles in the Chief Inspector Chen Cao series; how will the series evolve in the future?

So far I have published eleven titles in the Inspector Chen series. For reasons you may understand, I have tried not to be specific about the time period for each of the books, but generally speaking, with the first one set in the early nineties, the rest of the books follow the chronological order. So Inspector Chen has also been an evolving character. In THE DEATH OF A RED HEROINE, for instance, he’s still idealistic about the future of China in reform, and about his capability of making a difference by working as a conscientious cop. But in the following books, he has been getting more and more disillusioned. In the last couple of books, he has been removed from his position as a chief inspector in the Shanghai Police Bureau, and appointed at another position in a new office with no real power. With so many things happening in China, however, Chen still wants to investigate in his way, and in the latest Chen book (temporally titled INSPECTOR CHEN AND THE PRIVATE KITCHEN DINNER MURDER in English forthcoming in June), Chen has to investigate under the cover of writing a Judge Dee novella (forthcoming in December), and the two investigations in parallel complementing and commenting on each other: no independent judiciary in the ancient China, and in the contemporary China.

Your detective series has been very well-received and won many awards, and has been translated into the major European languages. Why has the series been so popular in Europe?

My European publishers have done great jobs, I think. During my book tours of these countries, I have noticed one thing different in European bookstores. They carry a lot more translated books than in U.S. bookstores. Some critics told me that European readers are more interested in what’s happening in other cultures or countries, but it may of course be too simplistic to say that.

Several of your titles have been translated from English into Chinese. Have your Chinese publishers requested changes, or have you been able to remain true to the English original?

Yes, several of my titles have been translated into Chinese. When my Chinese publishers first contacted me, I was doubtful about its translation into Chinese, but they assured me that China had changed, and that the translations would not have any problems. But they did encounter problems. Before publication, the censorship officials declared that the murder case cannot have happened in Shanghai, so they had to change Shanghai to H City in Chinese. The logic is simple: bad things like murder or corruption may be possible in fiction, but not in a real city of China. For the same reason, they changed the names of the streets, hotels for fear that readers may still recognize that these are stories set in Shanghai, China. What’s worse, they even changed the ending of the first book. Because of that, I decided not to have Inspector Chen books translated and published in China any more.

What insights into Chinese society and its political system can someone who is interested in modern China get from reading about modern Chinese crime which they are not likely to get elsewhere?

To explore the problems in the Chinese society and its political system, who can be more convenient and observant than a cop walking about in the city, knocking on the doors, raising questions to people in all walks of life, and trying to find the answers despite the setbacks? As a cop, Chen may also have access to some inside information under the one-Party system, but as an intellectual influenced by the modernist literature in the west, Chen cannot but question the system in which he has to struggle for survival.

Footnotes:

Qiu Xiaolong author website

Next Week: The Korean (North and South) connection in China

Just finished his first Inspector Chen Cao's novel, "The Death of a Red Heroine" and enjoyed it. It gives insights into how the opening of the Chinese economy in the early '90's begins to have profound effects on society. Some of the examples are metaphors for the decisions of the younger generation to eschew traditional values in their pursuit of money and a better life. The ending was fascinating showing the trade-offs between what would be considered "justice" versus keeping the tea pot from exploding within the upper ranks of the CCP – I think this part was a bit different from your typical "who-done-it" – less of a confrontational showdown. I'm sure I didn't pick up on every nuance and insight but found it enjoyable anyways.

Just downloaded the first of his books to my Kindle, I am looking forward to this.......